12.11.25

•

Avi Patel

The Uncanny Valley of Perfection

The Uncanny Valley of Perfection

The Uncanny Valley of Perfection

12 MIN READ

COMPUTER VISION

Introduction

State-of-the-art (SOTA) image generation models tend to have aesthetic mode collapses. Tuning often biases models like Flux.1 or SDXL toward a ‘studio-definition’ local minimum — resulting in images that lack the chaotic entropy of camera physics, including photon noise, lens aberrations, and motion blur. Models often overlay smooth or predictable noise on top of geometries to simulate the effect of a camera, or optimize for these rendering components in overly reductive ways.

In this pilot experiment, we investigate whether we can shift this bias and jointly model the optical factors of consumer camera sensors in a way that base or prompt-engineered models cannot. We curated a high-utility coreset of 3100 real-world images using a VAE-based influence scoring metric, with the intuition that images with high reconstruction loss but high semantic coherence would force the model to learn the ‘long tail’ of realistic texture distribution. We then finetuned SDXL and Flux.1-dev for 3 epochs (null-conditioned). To contextualize and validate our results, we had two controls sourced from real-world images: low-trust/quality data (often random, exceedingly noisy images that would degrade a model) and a held-out high-trust data. We produced the following test splits:

State-of-the-art (SOTA) image generation models tend to have aesthetic mode collapses. Tuning often biases models like Flux.1 or SDXL toward a ‘studio-definition’ local minimum — resulting in images that lack the chaotic entropy of camera physics, including photon noise, lens aberrations, and motion blur. Models often overlay smooth or predictable noise on top of geometries to simulate the effect of a camera, or optimize for these rendering components in overly reductive ways.

In this pilot experiment, we investigate whether we can shift this bias and jointly model the optical factors of consumer camera sensors in a way that base or prompt-engineered models cannot. We curated a high-utility coreset of 3100 real-world images using a VAE-based influence scoring metric, with the intuition that images with high reconstruction loss but high semantic coherence would force the model to learn the ‘long tail’ of realistic texture distribution. We then finetuned SDXL and Flux.1-dev for 3 epochs (null-conditioned). To contextualize and validate our results, we had two controls sourced from real-world images: low-trust/quality data (often random, exceedingly noisy images that would degrade a model) and a held-out high-trust data. We produced the following test splits:

Base Model: Zero-shot generation.

Prompt Engineering (PE): appending variations of phrases such as "Style: shot on iPhone, natural lighting, casual photo, smartphone camera".

Fine-Tuning (LoRA) (same prompting as the base model).

Base Model: Zero-shot generation.

Prompt Engineering (PE): appending variations of phrases such as "Style: shot on iPhone, natural lighting, casual photo, smartphone camera".

Fine-Tuning (LoRA) (same prompting as the base model).

Each of these were further stratified into in-distribution (ID) (ex. people walking, a car on a street) and out-of-distribution (OOD) (ex. a microscope, boat on a lake) sets relative to the finetuning content for fair comparison of style generalization.

Each of these were further stratified into in-distribution (ID) (ex. people walking, a car on a street) and out-of-distribution (OOD) (ex. a microscope, boat on a lake) sets relative to the finetuning content for fair comparison of style generalization.

Results

Our results offer nascent, but encouraging support to pursue this line of exploration. We treat this as intermediate validation as opposed to a definitive benchmark, for reasons outlined in the Discussion. We look at a wide set of metrics to characterize effects:

Our results offer nascent, but encouraging support to pursue this line of exploration. We treat this as intermediate validation as opposed to a definitive benchmark, for reasons outlined in the Discussion. We look at a wide set of metrics to characterize effects:

Distributional: FID to the high-trust set — a standard metric to characterize multivariate distance between generated and high-trust reference sets.

Human-proxy: Aesthetics (CLIP-MLP scoring) — a measurement of perceived photographic quality that correlates with human judgment. Note that this can be gameable, and that the noise of real images tends to produce lower aesthetic scores compared to generated images. However, it is necessary to ensure complete image degradation does not occur.

Microstructure: spectral slope (power spectrum) and decay, noise kurtosis, sensor banding, edge coherence stats, compression artifact counts, depth coherence. These characterize image noise and frequency patterns. Natural photographic scenes and sensors have signature patterns which differ from synthetic smoothing or ad-hoc noise. Edge properties and depth coherence are key to geometric realism.

Structural preservation and perceptual diversity: DINO, LPIPS. These are guardrails to ensure that we do not deform key elements in the image, nor destroy the desired visual choices or range for a given task.

Distributional: FID to the high-trust set — a standard metric to characterize multivariate distance between generated and high-trust reference sets.

Human-proxy: Aesthetics (CLIP-MLP scoring) — a measurement of perceived photographic quality that correlates with human judgment. Note that this can be gameable, and that the noise of real images tends to produce lower aesthetic scores compared to generated images. However, it is necessary to ensure complete image degradation does not occur.

Microstructure: spectral slope (power spectrum) and decay, noise kurtosis, sensor banding, edge coherence stats, compression artifact counts, depth coherence. These characterize image noise and frequency patterns. Natural photographic scenes and sensors have signature patterns which differ from synthetic smoothing or ad-hoc noise. Edge properties and depth coherence are key to geometric realism.

Structural preservation and perceptual diversity: DINO, LPIPS. These are guardrails to ensure that we do not deform key elements in the image, nor destroy the desired visual choices or range for a given task.

We paired evaluation with the same RNG seeds for robust comparison, and computed bootstrapped CIs and permutation tests where applicable. In prompt-set analyses, we use CLIP to match text embeddings (and verify with metadata matching) and identify relevant high-trust data to serve an approximate ground truth (GT) for each prompt. We then compute KDE distributions, improvements (relative to the GT set) of finetuning over PE and the base model using both median and Wasserstein-1 distance; we display Wasserstein-1 here, though both were consistent with each other.

We paired evaluation with the same RNG seeds for robust comparison, and computed bootstrapped CIs and permutation tests where applicable. In prompt-set analyses, we use CLIP to match text embeddings (and verify with metadata matching) and identify relevant high-trust data to serve an approximate ground truth (GT) for each prompt. We then compute KDE distributions, improvements (relative to the GT set) of finetuning over PE and the base model using both median and Wasserstein-1 distance; we display Wasserstein-1 here, though both were consistent with each other.

SDXL

SDXL offers a noticeable movement in distribution toward the photo reference set across the physical metrics across both ID and OOD sets. Looking at FID scores (lower is better), we see -15.78 (ID-Tuned vs ID-Base) and -4.46 (ID-Tuned vs ID-PE) shifts in aggregate. Across DINO and LPIPS scores, we find that image structure and diversity remains stable.

SDXL offers a noticeable movement in distribution toward the photo reference set across the physical metrics across both ID and OOD sets. Looking at FID scores (lower is better), we see -15.78 (ID-Tuned vs ID-Base) and -4.46 (ID-Tuned vs ID-PE) shifts in aggregate. Across DINO and LPIPS scores, we find that image structure and diversity remains stable.

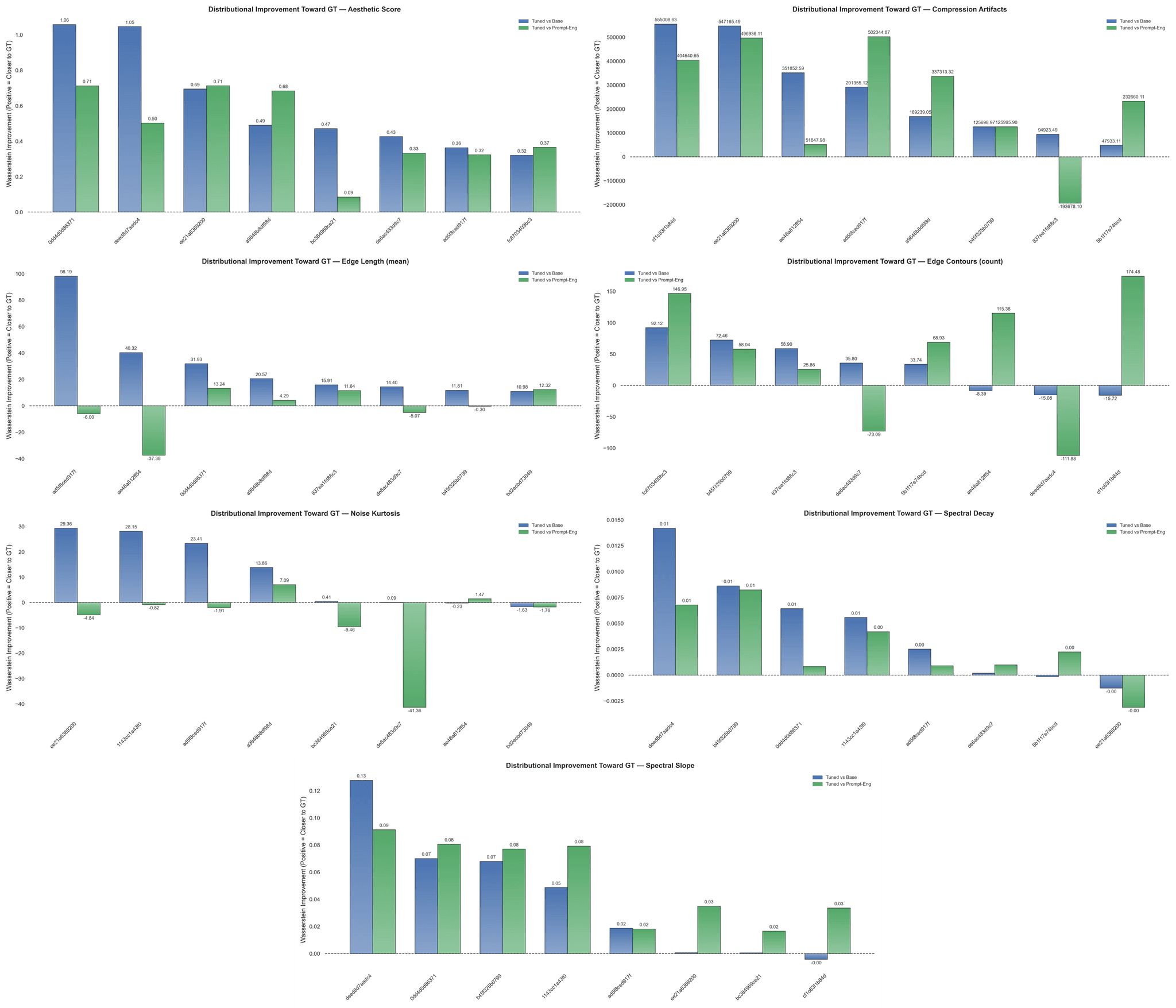

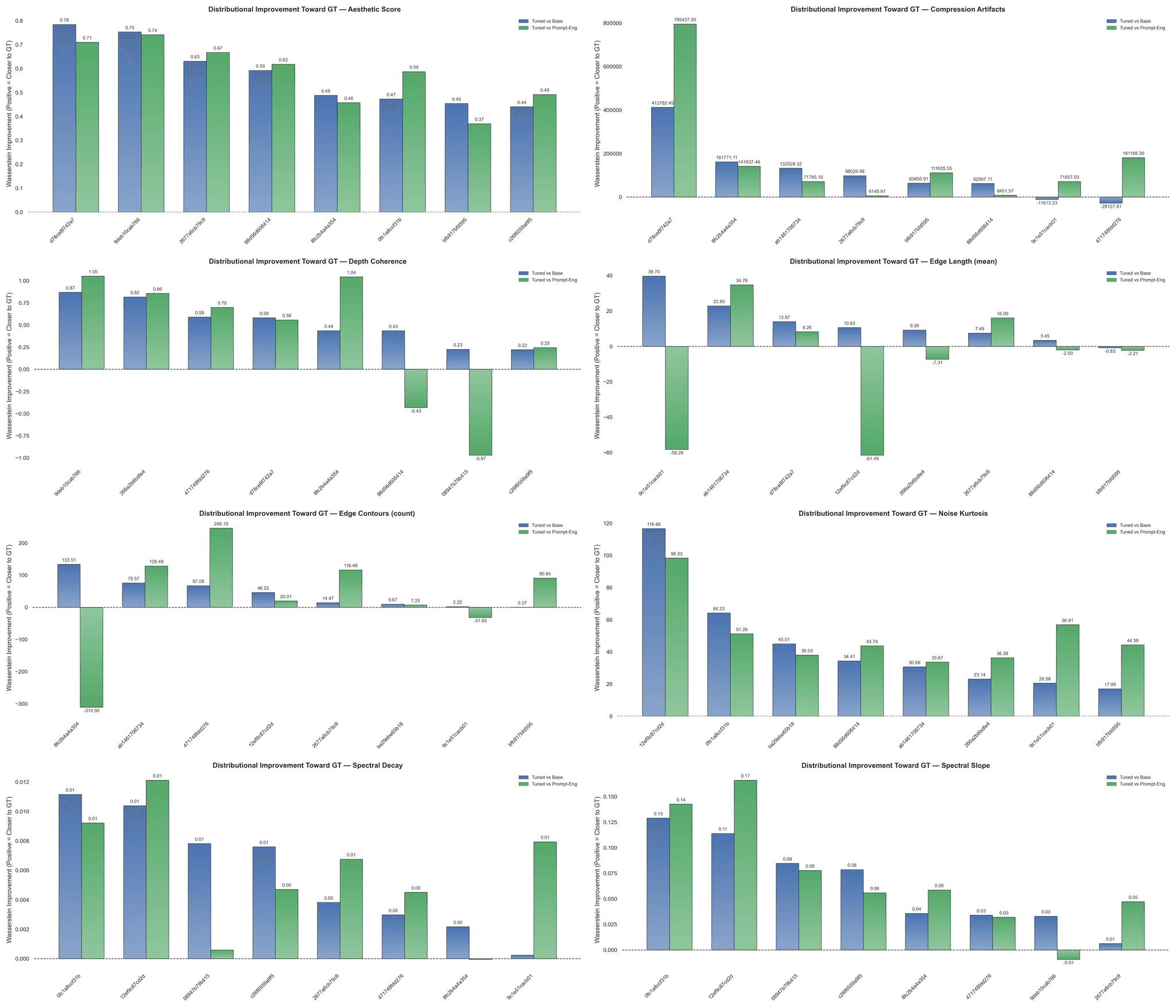

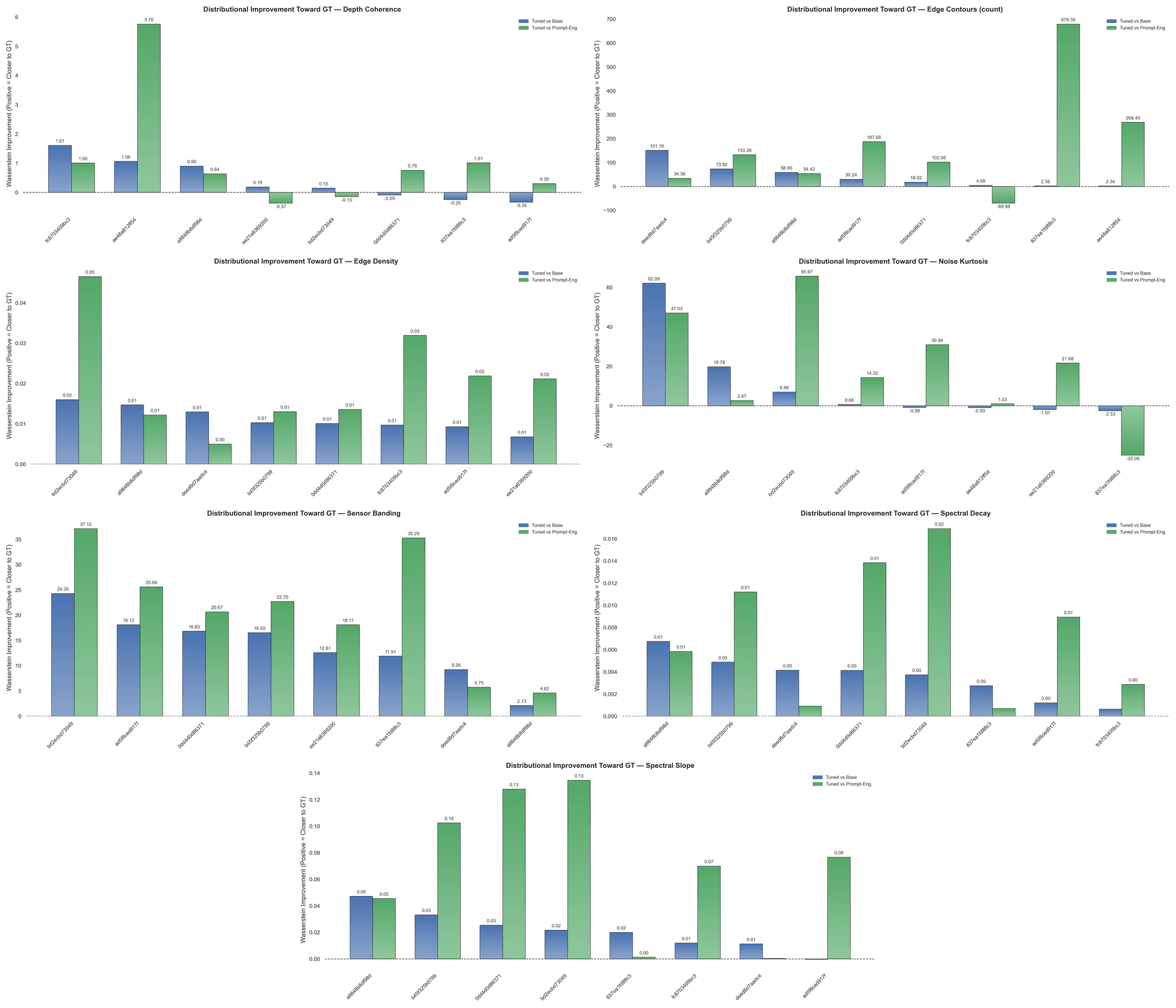

SDXL ID

Figure 1: Wasserstein-1 Distance Improvements [Blue – Tuned over Base, Green – Tuned over PE] for (left-to-right): Aesthetic Score, Compression Artifacts, Edge Length, Edge Contours, Noise Kurtosis, Spectral Decay, and Spectral Slope.

Figure 1: Wasserstein-1 Distance Improvements [Blue – Tuned over Base, Green – Tuned over PE] for (left-to-right): Aesthetic Score, Compression Artifacts, Edge Length, Edge Contours, Noise Kurtosis, Spectral Decay, and Spectral Slope.

We find that the aesthetic scores improved uniformly toward the GT set, but note that in the absolute sense: the distribution of aesthetic scores in our real images centers around 4.5 (1–10 scale, higher is better) while generated images cluster around 5.5. Frequency content similarly demonstrates a systematic movement toward GT, attenuating synthetic high frequencies and restoring the more characteristic 1/f falloff observed in camera images. Edge statistics exhibited corrections — edge length and contour counts increased, implying potentially more physically coherent geometries were adopted. Evaluating noise kurtosis suggests that heavy-tailed noise was significantly reduced, in aggregate overcorrecting from 71.72 to a mean of 36.38, with GT sitting at 50.75. Expectedly, the finetuned model replicates the periodic compression artifacts present in the data — a positive effect if pursuing hyper photo-realism, but a negative aesthetic choice. In a small subset of test images, compression artifacts were amplified — a key failure mode, though one rectified by introducing a penalty or gating series during finetuning. We observe that depth coherence is not improved relative to the base. Curiously, despite finetuning a dataset with higher sensor-banding (~66.83) relative to the controls, the finetuned output displays fewer banding artifacts (-5–15) compared to the ID-Base/PE. We posit that there may be tension between the denoising objective and the low-level noise pattern, leading to its suppression — a positive outcome for perceptual realism, but a negative one for faithful sensor replication. Cumulatively, the bulk behavior indicates a reassuring, GT-aligned improvement.

We find that the aesthetic scores improved uniformly toward the GT set, but note that in the absolute sense: the distribution of aesthetic scores in our real images centers around 4.5 (1–10 scale, higher is better) while generated images cluster around 5.5. Frequency content similarly demonstrates a systematic movement toward GT, attenuating synthetic high frequencies and restoring the more characteristic 1/f falloff observed in camera images. Edge statistics exhibited corrections — edge length and contour counts increased, implying potentially more physically coherent geometries were adopted. Evaluating noise kurtosis suggests that heavy-tailed noise was significantly reduced, in aggregate overcorrecting from 71.72 to a mean of 36.38, with GT sitting at 50.75. Expectedly, the finetuned model replicates the periodic compression artifacts present in the data — a positive effect if pursuing hyper photo-realism, but a negative aesthetic choice. In a small subset of test images, compression artifacts were amplified — a key failure mode, though one rectified by introducing a penalty or gating series during finetuning. We observe that depth coherence is not improved relative to the base. Curiously, despite finetuning a dataset with higher sensor-banding (~66.83) relative to the controls, the finetuned output displays fewer banding artifacts (-5–15) compared to the ID-Base/PE. We posit that there may be tension between the denoising objective and the low-level noise pattern, leading to its suppression — a positive outcome for perceptual realism, but a negative one for faithful sensor replication. Cumulatively, the bulk behavior indicates a reassuring, GT-aligned improvement.

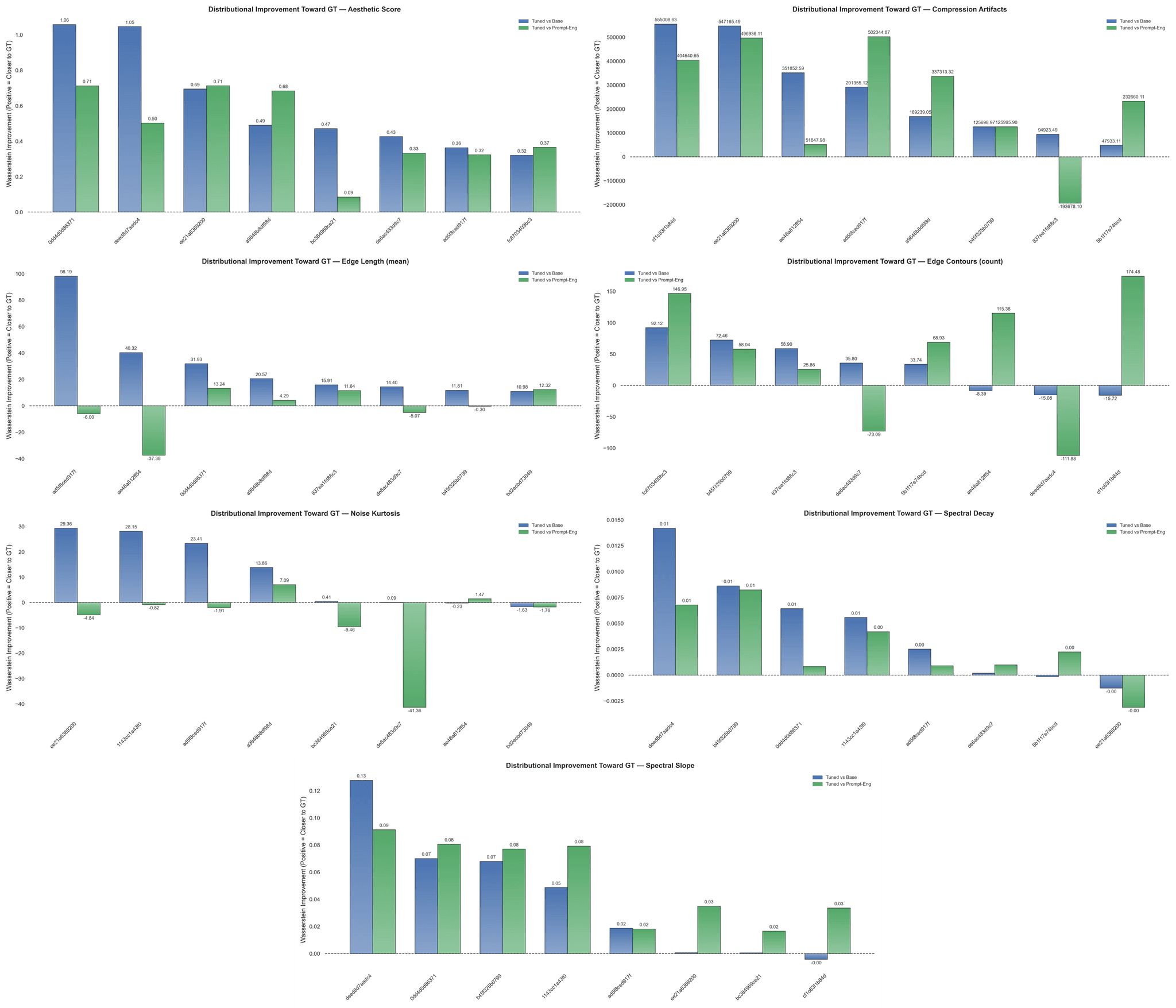

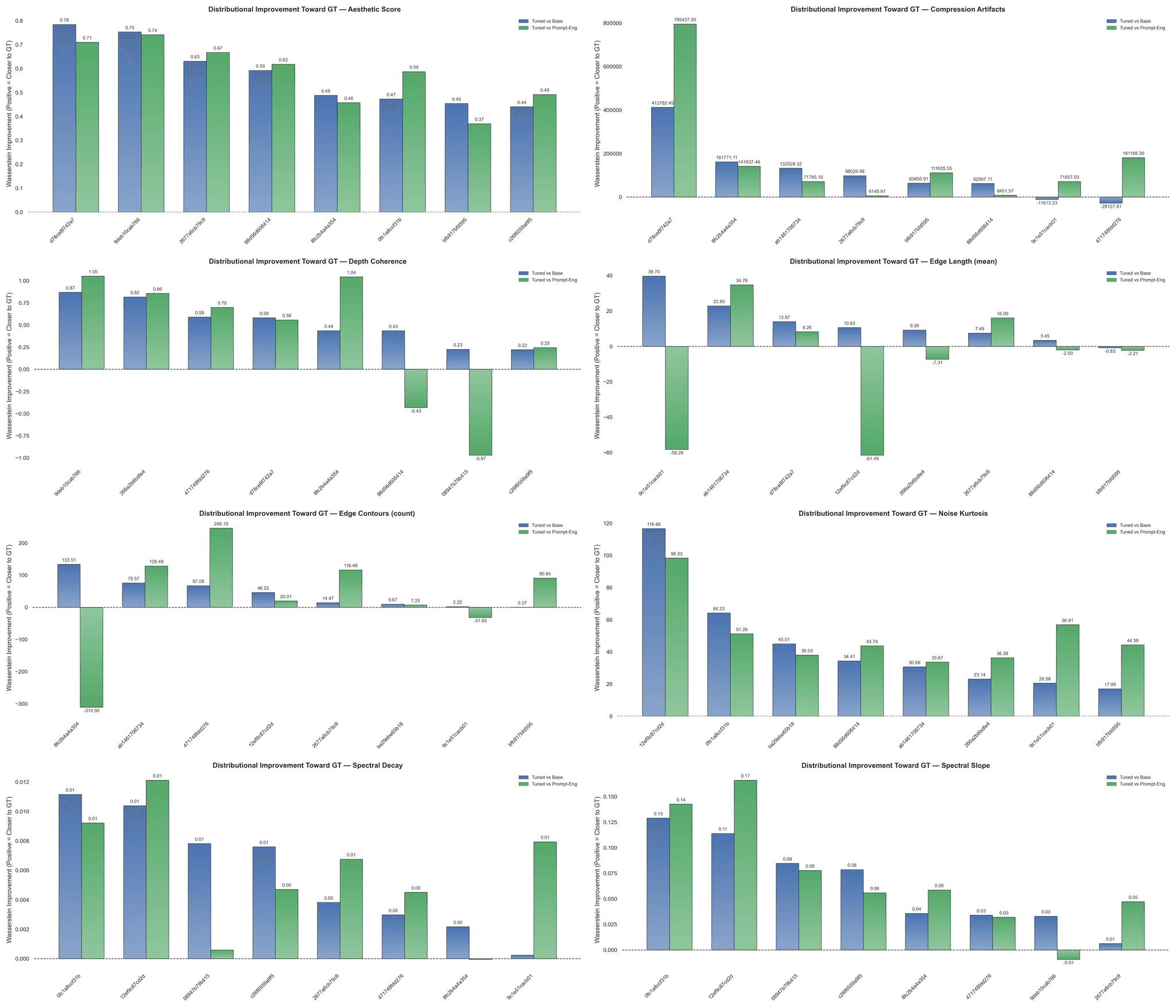

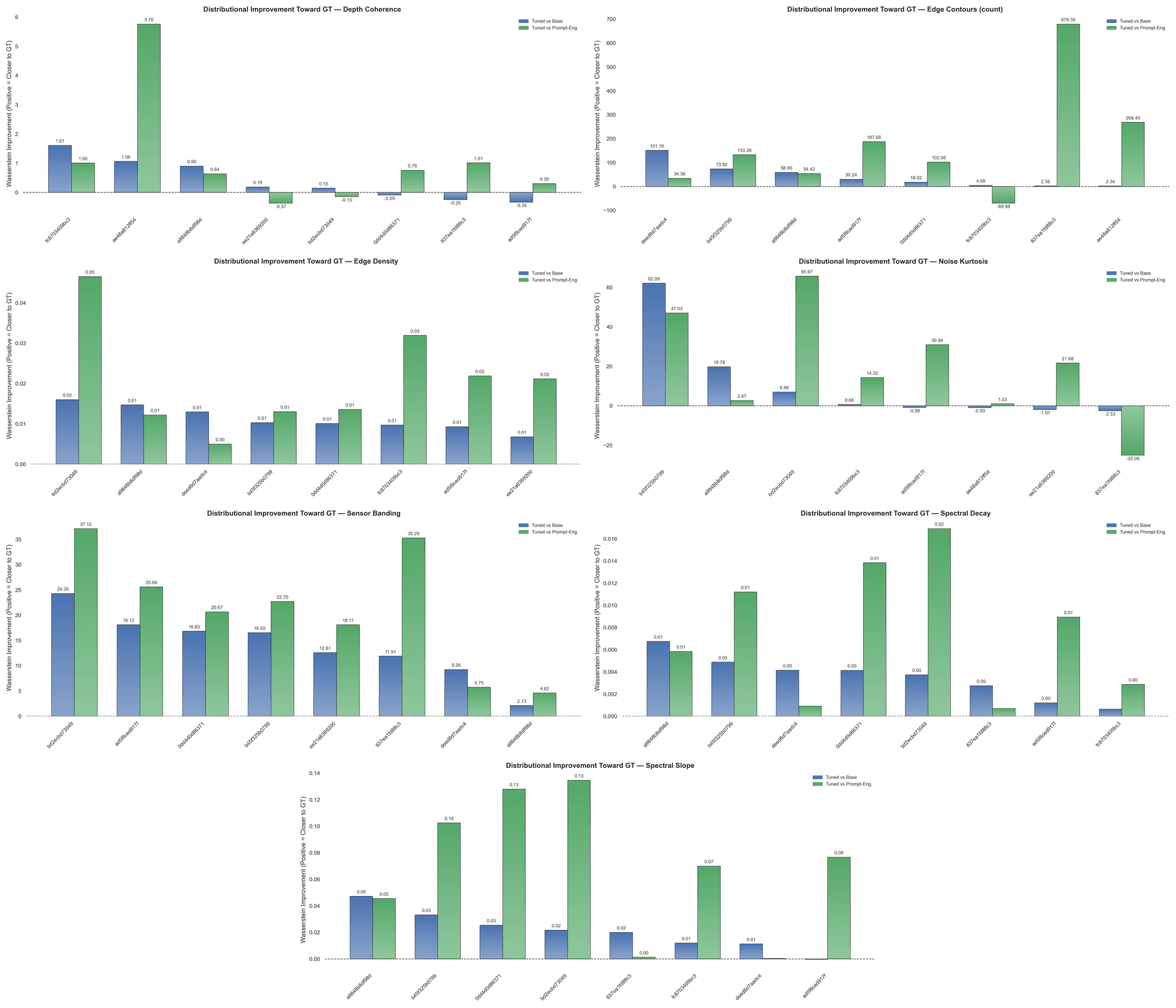

SDXL OOD

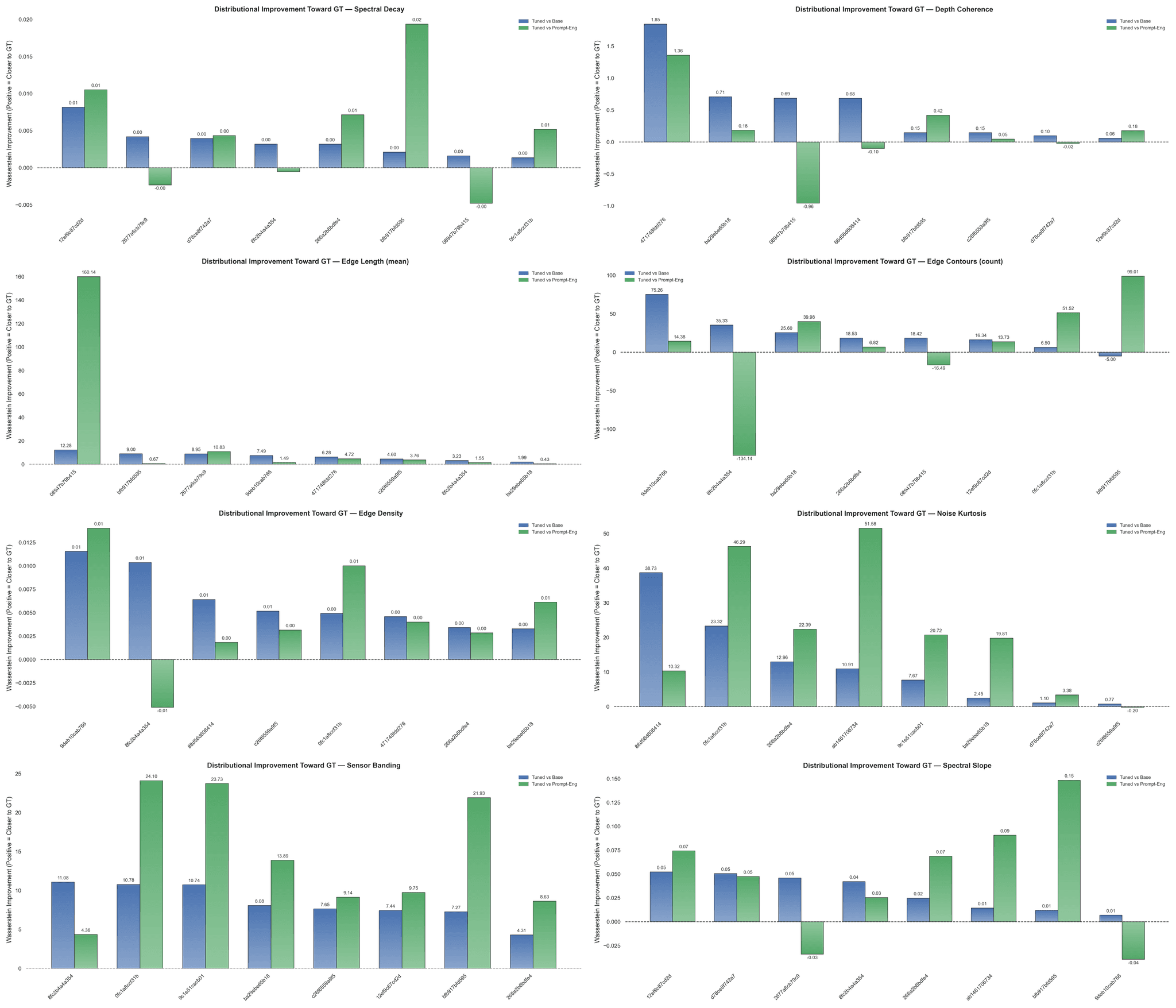

Figure 2: Wasserstein-1 Distance Improvements [Blue – Tuned over Base, Green – Tuned over PE] for (left-to-right): Aesthetic Score, Compression Artifacts, Depth Coherence, Edge Length, Edge Contours, Noise Kurtosis, Spectral Decay, and Spectral Slope.

Figure 2: Wasserstein-1 Distance Improvements [Blue – Tuned over Base, Green – Tuned over PE] for (left-to-right): Aesthetic Score, Compression Artifacts, Depth Coherence, Edge Length, Edge Contours, Noise Kurtosis, Spectral Decay, and Spectral Slope.

The OOD set seems to replicate many of the behaviors seen in the ID set: shifted aesthetic scores, compression artifacts, reduced noise tailing, and more natural spectral features compared to base and PE outputs. Improvements in edge statistics are much less pronounced here — a potential reason being the significant disparity in the structures and objects present in this set compared to the learned priors. Curiously, depth coherence exhibits consistent movement toward GT over the base and PE — something missing in the ID set. An (perhaps overly) optimistic explanation is that in-context, the bias is stronger and more likely to misalign or conflict with the scene geometry, while out-of-context, the bias acts more akin to a smoothing or regularizing geometric prior. This would fit well with the fact that, empirically, indoor-trained depth nets generalize surprisingly well to outdoor scenes by shifting to reliance on these priors.

The OOD set seems to replicate many of the behaviors seen in the ID set: shifted aesthetic scores, compression artifacts, reduced noise tailing, and more natural spectral features compared to base and PE outputs. Improvements in edge statistics are much less pronounced here — a potential reason being the significant disparity in the structures and objects present in this set compared to the learned priors. Curiously, depth coherence exhibits consistent movement toward GT over the base and PE — something missing in the ID set. An (perhaps overly) optimistic explanation is that in-context, the bias is stronger and more likely to misalign or conflict with the scene geometry, while out-of-context, the bias acts more akin to a smoothing or regularizing geometric prior. This would fit well with the fact that, empirically, indoor-trained depth nets generalize surprisingly well to outdoor scenes by shifting to reliance on these priors.

Flux

Finetuned Flux produces stable, distributional improvements over the base model. Crucially, it consistently reduces the variance and failure modes that prompt engineering exhibits, with improvements on spectral and texture-based metrics. This holds for both ID and OOD prompts, though magnitudes and risk-profile differ. However, we identify no changes competitive with PE or sufficiently above the base model in terms of aesthetic score, structure preservation (DINO scores), and FID. We further note that the image diversity (LPIPS) is preserved.

Finetuned Flux produces stable, distributional improvements over the base model. Crucially, it consistently reduces the variance and failure modes that prompt engineering exhibits, with improvements on spectral and texture-based metrics. This holds for both ID and OOD prompts, though magnitudes and risk-profile differ. However, we identify no changes competitive with PE or sufficiently above the base model in terms of aesthetic score, structure preservation (DINO scores), and FID. We further note that the image diversity (LPIPS) is preserved.

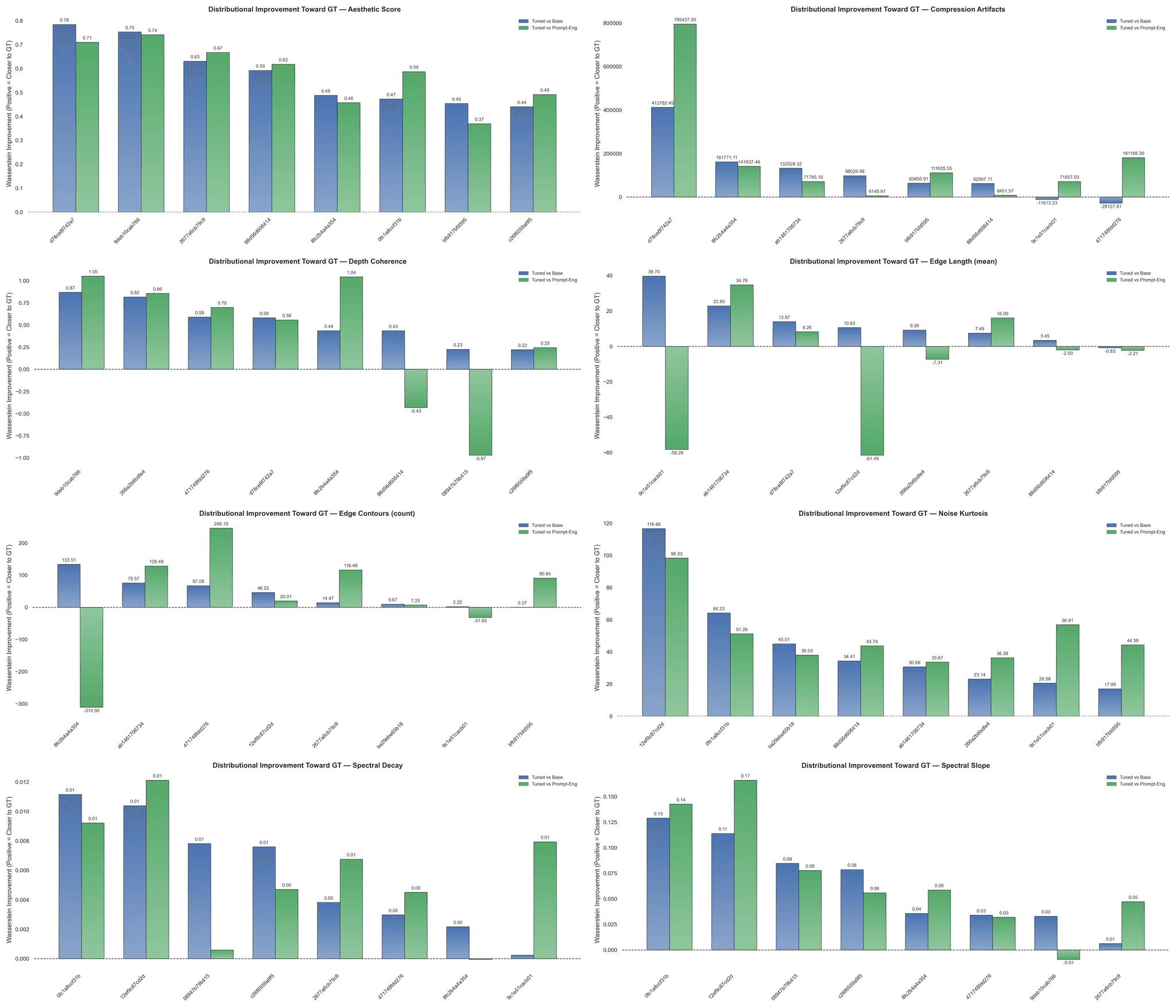

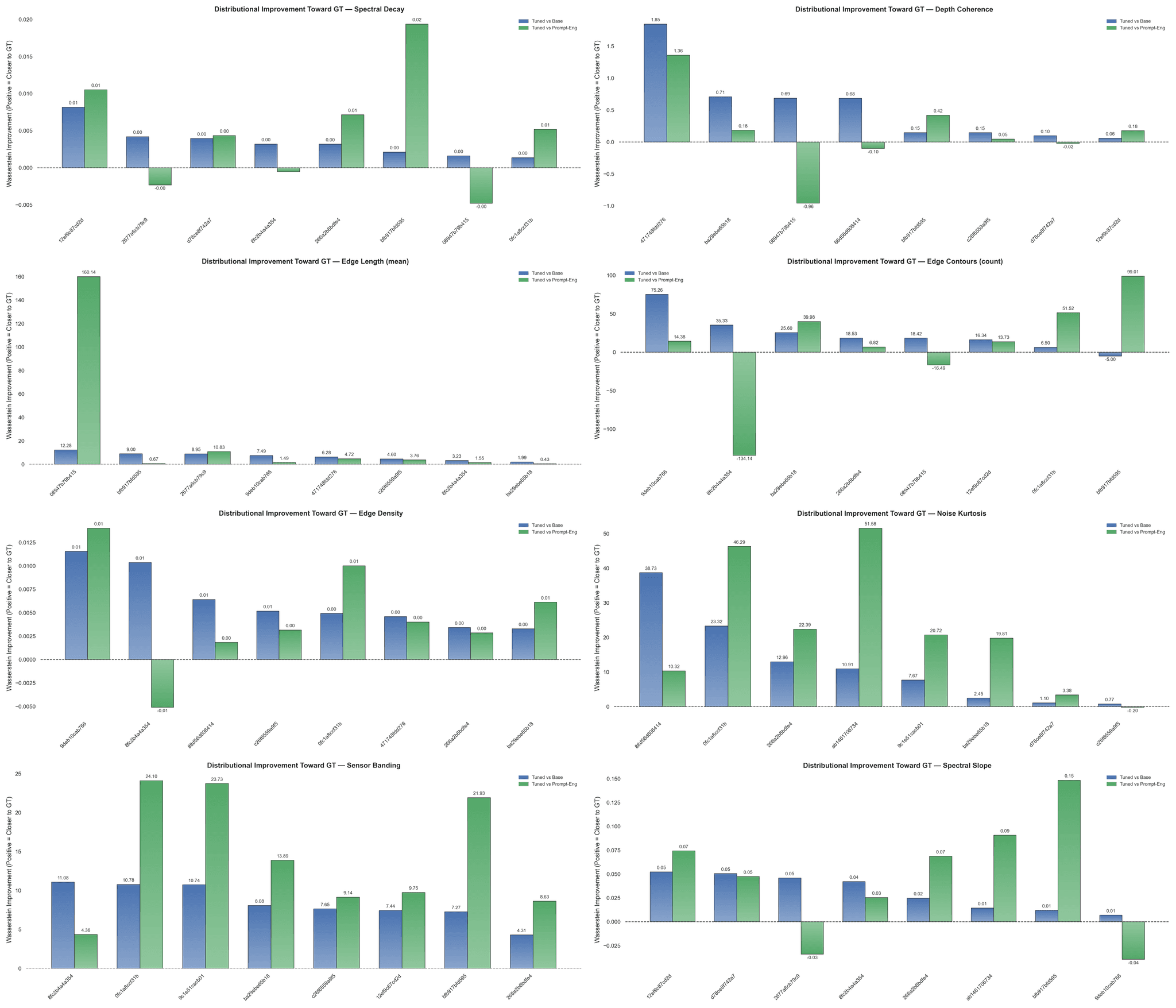

Flux ID

Figure 3: Wasserstein-1 Distance Improvements [Blue – Tuned over Base, Green – Tuned over PE] for (left-to-right): Depth Coherence, Edge Contours, Edge Density, Noise Kurtosis, Sensor Banding, Spectral Decay, and Spectral Slope.

Figure 3: Wasserstein-1 Distance Improvements [Blue – Tuned over Base, Green – Tuned over PE] for (left-to-right): Depth Coherence, Edge Contours, Edge Density, Noise Kurtosis, Sensor Banding, Spectral Decay, and Spectral Slope.

Flux’s LoRA consistently shifted image-level microstructure statistics and frequencies — spectral slope and decay, banding, edge density and contours, and noise kurtosis – closer to the high-trust prompt-matched distribution. This improvement is both larger and more stable than prompt engineering, which shows considerable variance. We further noticed a minor effect on depth coherence — causal analysis is needed to understand the factors underlying its variation.

Flux’s LoRA consistently shifted image-level microstructure statistics and frequencies — spectral slope and decay, banding, edge density and contours, and noise kurtosis – closer to the high-trust prompt-matched distribution. This improvement is both larger and more stable than prompt engineering, which shows considerable variance. We further noticed a minor effect on depth coherence — causal analysis is needed to understand the factors underlying its variation.

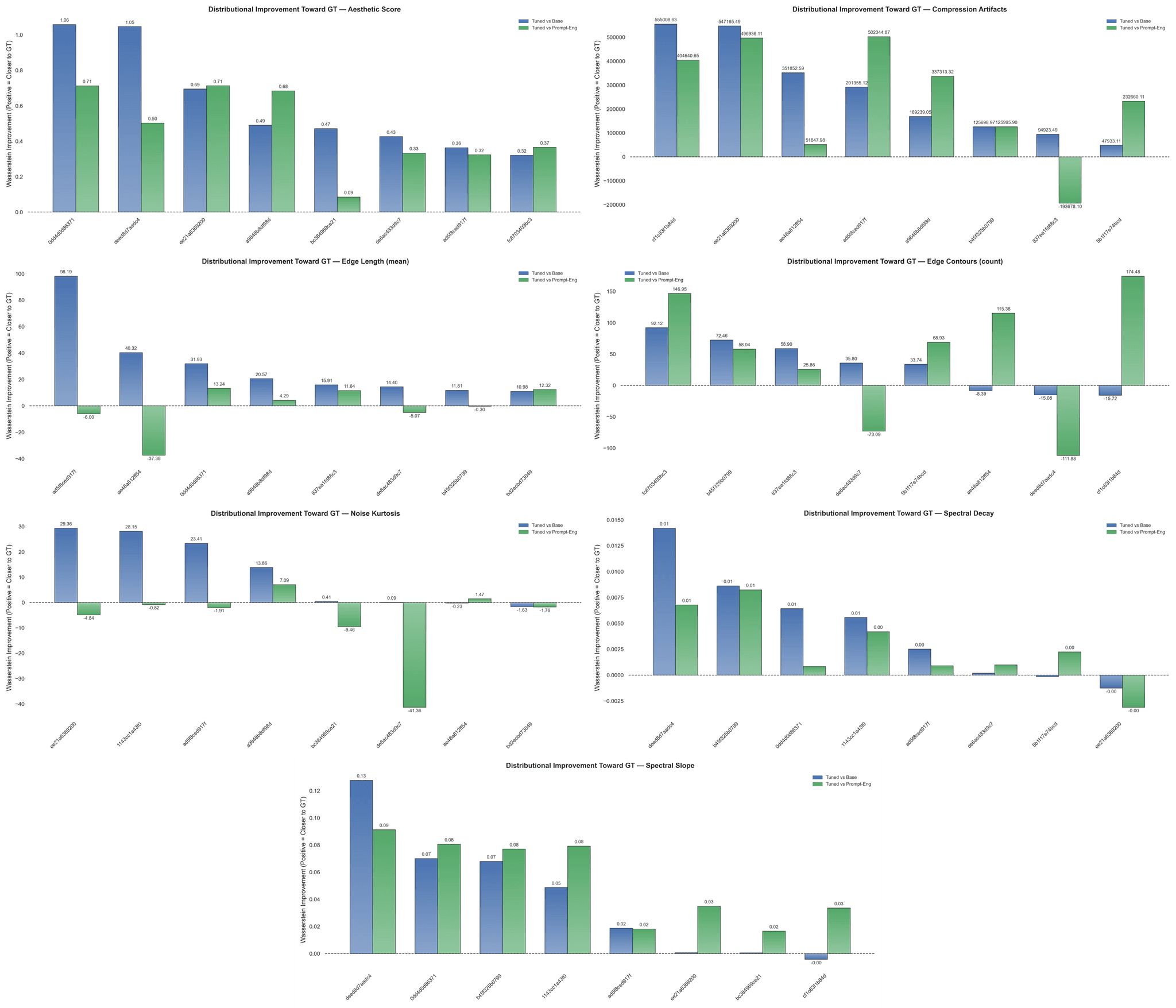

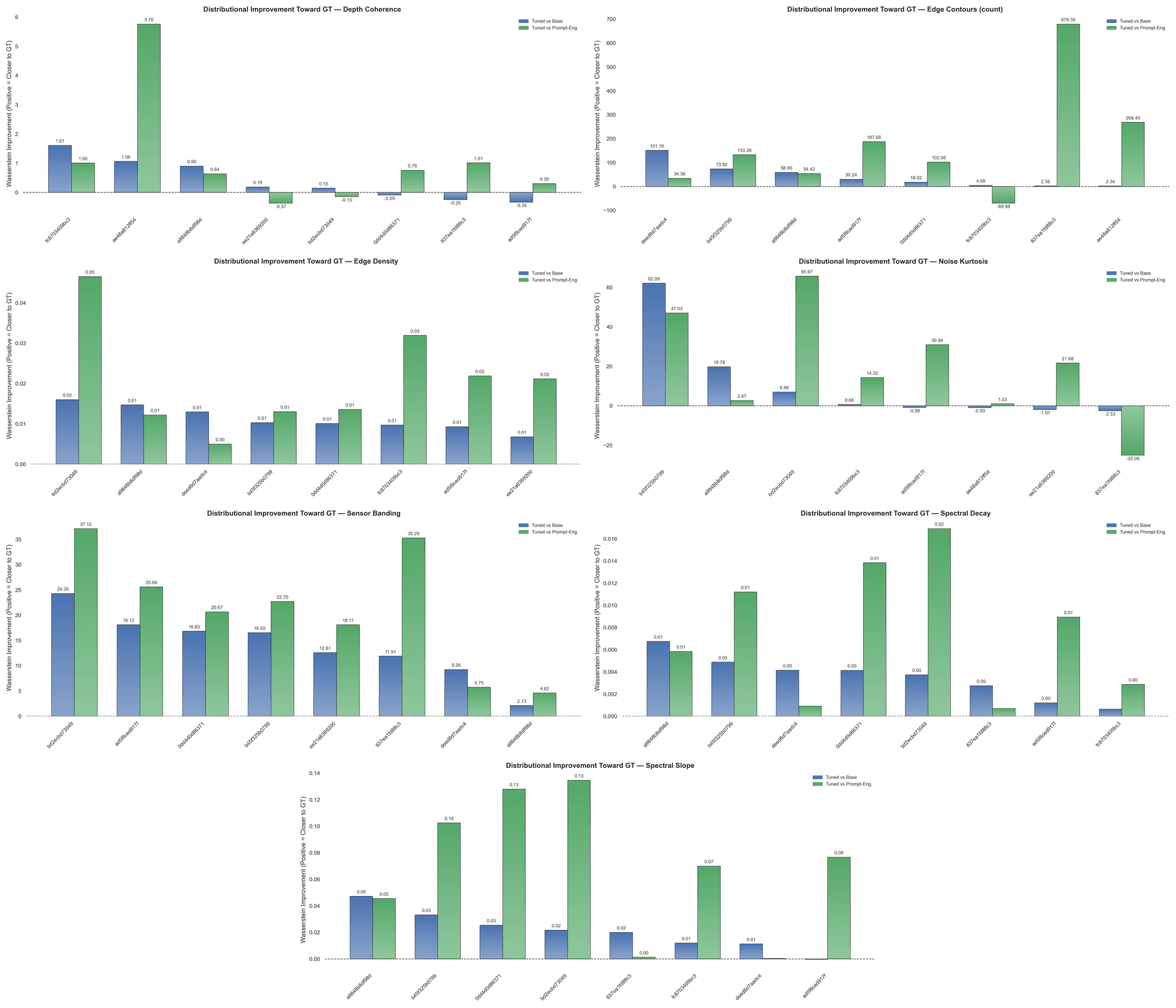

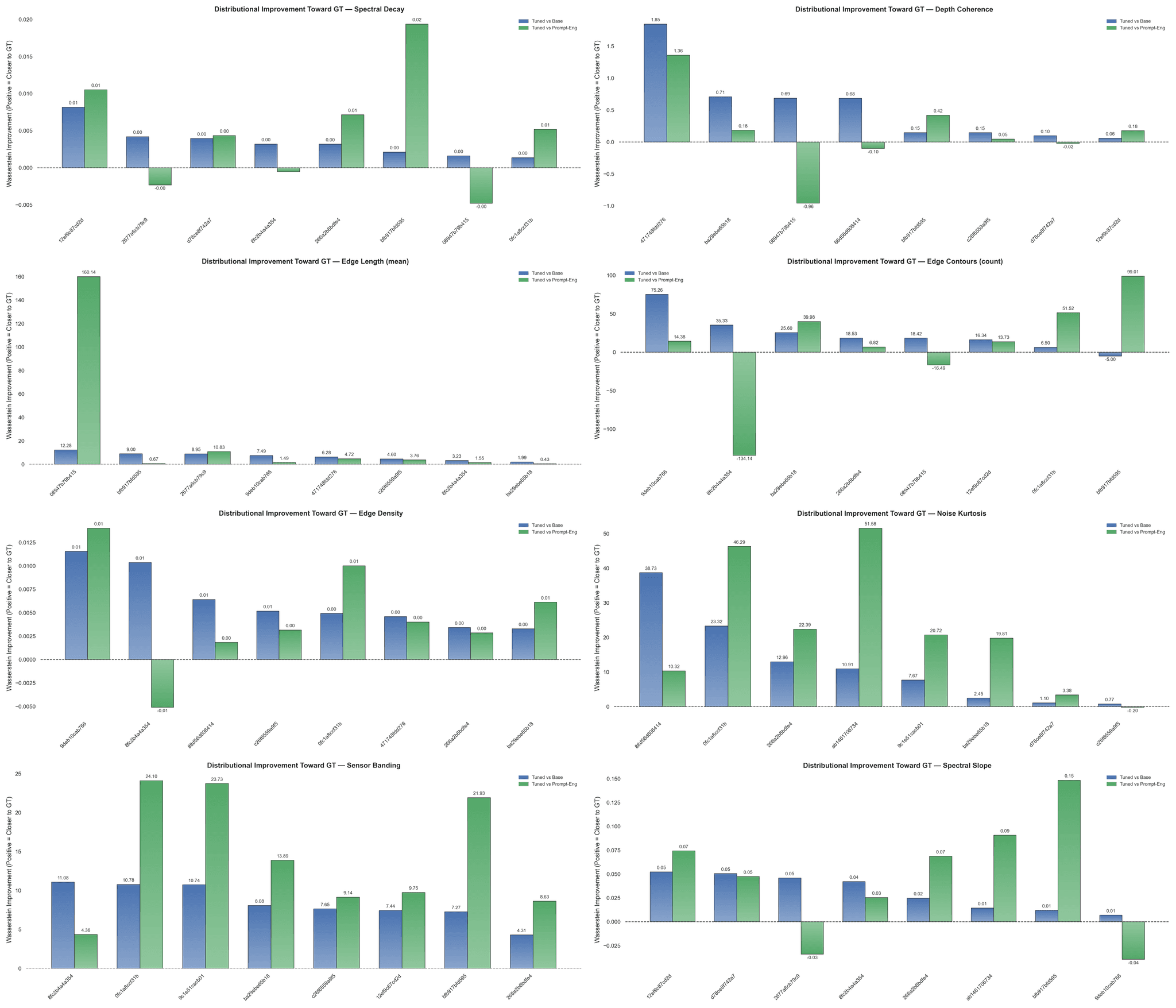

Flux OOD

Figure 4: Wasserstein-1 Distance Improvements [Blue – Tuned over Base, Green – Tuned over PE] for (left-to-right): Spectral Decay, Depth Coherence, Edge Length, Edge Contours, Edge Density, Noise Kurtosis, Sensor Banding, and Spectral Slope.

Figure 4: Wasserstein-1 Distance Improvements [Blue – Tuned over Base, Green – Tuned over PE] for (left-to-right): Spectral Decay, Depth Coherence, Edge Length, Edge Contours, Edge Density, Noise Kurtosis, Sensor Banding, and Spectral Slope.

Finetuned Flux consistently reduces EMD distance to the reference despite semantic content differing substantially from the finetune corpus, suggesting that physical texture signals — how noise power scales with frequency, periodic banding patterns, and more — were learned and seemingly translated across contexts. Prompt engineering continues to demonstrate sizable variability — with an overwhelming incidence of divergence from GT across this set of metrics.

Finetuned Flux consistently reduces EMD distance to the reference despite semantic content differing substantially from the finetune corpus, suggesting that physical texture signals — how noise power scales with frequency, periodic banding patterns, and more — were learned and seemingly translated across contexts. Prompt engineering continues to demonstrate sizable variability — with an overwhelming incidence of divergence from GT across this set of metrics.

Discussion

We find that finetuning on camera roll data yields distributional improvement on microstructure properties while reducing variance relative to prompt engineering. For a non-trivial subset of OOD prompts, the adapter shifts these metrics closer to the real set, indicating a form of more generic physics/texture priors were learned by the models as opposed to memorized artifacts or content. The dominant changes are in the spectral properties, kurtosis of residual noise, banding strength, and edge statistics — i.e., the adapter appears to have learned to manipulate mid/high-frequency texture components rather than only altering global tone. Interestingly, a brief interpretability sanity check on the finetuned SDXL model using PCA and singular-vector probing across the updated layers suggests that the learned update resides in a multi-dimensional diffuse subspace, rather than concentrating across a few principal directions. Anecdotally, this pattern is typical of adapters that capture a broad spectrum of texture or frequency priors instead of discrete semantic concepts.

We find that finetuning on camera roll data yields distributional improvement on microstructure properties while reducing variance relative to prompt engineering. For a non-trivial subset of OOD prompts, the adapter shifts these metrics closer to the real set, indicating a form of more generic physics/texture priors were learned by the models as opposed to memorized artifacts or content. The dominant changes are in the spectral properties, kurtosis of residual noise, banding strength, and edge statistics — i.e., the adapter appears to have learned to manipulate mid/high-frequency texture components rather than only altering global tone. Interestingly, a brief interpretability sanity check on the finetuned SDXL model using PCA and singular-vector probing across the updated layers suggests that the learned update resides in a multi-dimensional diffuse subspace, rather than concentrating across a few principal directions. Anecdotally, this pattern is typical of adapters that capture a broad spectrum of texture or frequency priors instead of discrete semantic concepts.

Limitations & Next Steps

Developing a rigorous finetuning pipeline — hyperparameter searches, image gating (curriculum learning), differentiable penalties, etc. — is necessary to improve confidence in the results and avoid inadvertent image degradation, especially in newer rectified flow transformer models. In a similar vein, we finetuned models with null-conditioning — we suspect that explicit semantic/text-conditioning or other adjustments may easily improve the effect of the data and stability of the model. While we report success across a significant majority of sets and metrics, a modest fraction of prompt-sets demonstrate artifact amplification. Relatedly, we’re evaluating the models on a set of implicitly nonlinearly correlating objectives (ex. aesthetic vs noise and edge-based properties, LPIPS vs FID, NIQE vs microstructure statistics), which poses a set of difficulties relating to model stability, finetuning regimen, and Pareto navigation. Causal probing of texture patterns and attention would enable deeper understanding of the transformations and tradeoffs learned by the model. Additionally, while this is outside of the scope of our experiment, it should be noted that the hallucinatory aspects of image-generation models (e.g. physical inconsistencies) persist after finetuning.

Developing a rigorous finetuning pipeline — hyperparameter searches, image gating (curriculum learning), differentiable penalties, etc. — is necessary to improve confidence in the results and avoid inadvertent image degradation, especially in newer rectified flow transformer models. In a similar vein, we finetuned models with null-conditioning — we suspect that explicit semantic/text-conditioning or other adjustments may easily improve the effect of the data and stability of the model. While we report success across a significant majority of sets and metrics, a modest fraction of prompt-sets demonstrate artifact amplification. Relatedly, we’re evaluating the models on a set of implicitly nonlinearly correlating objectives (ex. aesthetic vs noise and edge-based properties, LPIPS vs FID, NIQE vs microstructure statistics), which poses a set of difficulties relating to model stability, finetuning regimen, and Pareto navigation. Causal probing of texture patterns and attention would enable deeper understanding of the transformations and tradeoffs learned by the model. Additionally, while this is outside of the scope of our experiment, it should be noted that the hallucinatory aspects of image-generation models (e.g. physical inconsistencies) persist after finetuning.

The Leading Data Marketplace.

Support

A Nitrility Inc. Company

Kled AI © 2025

The Leading Data Marketplace.

Support

A Nitrility Inc. Company

Kled AI © 2025

The Leading Data Marketplace.

Support

A Nitrility Inc. Company

Kled AI © 2025